.

In spite of the fact college

basketball is an amateur sport, there is nothing amateur about the way money is

generated from the NCAA playoffs. So

massive is the revenue that it far surpasses even the Super Bowl.

Perhaps a better gauge of popularity

is the amount people bet on the games and here

Las Vegas knows the winner. For every dollar bet on the Super Bowl, at

least seven dollars are bet during March Madness, well over $7 billion.

In fact, if you combine revenue from

the entire NFL playoffs including the Super Bowl, it is one third less than the

NCAA playoffs. If you combined all the

revenue from the professional NBA, Major League Baseball, and National Hockey

League playoffs, it is still one third less than the NCAA playoffs.

King Midas is alive and well in NCAA

country.

When it comes to college basketball,

one might be driven crazy by all the constant changes in conference members,

the odd television broadcast schedules, the incessant drive for perfection, and

the big business aspects.

There is a reason for these things

as big business is big bucks.

Of course in spite of all the

billions of dollars spent during March Madness, the players, those gladiators

in the ring, get nothing.

But ad revenue is just a small part of the story. Investopedia identifies four more

extremely lucrative ways the tournament makes money, none of which goes to the

players:

1) Broadcast rights: In April 2010, the NCAA inked a deal with CBS that made

the network its exclusive March Madness outlet. The contract lasts for 14 years

and is worth a whopping $10.8 billion. This contract alone is projected to

generate $771 million per year for the NCAA.

2) "The basketball fund": The NCAA's annual March Madness revenue

is divided among the different basketball-playing schools and conferences (i.e.

the Pac-12, SEC, etc.) based on factors such as schools' numbers of sports

teams, scholarships awarded and tournament performances.

Conferences also have a hand in divvying up these large money pots (between

2005 and 2011, the top-earning Big East conference made $86.7 million) either

evenly amongst schools or based on March Madness performance and revenue

generated. According to

Forbes, a team's trip to the Final Four

earns its conference $9.5 million.

3) Ticket sales and sponsorships: During March Madness, tickets and sponsors

generate about $40 million in revenue. Combined with the money from the

broadcast rights, this accounts for 96% of the NCAA's total annual revenue.

4) Wagers: What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, especially if it involves

an unlucky March Madness bet. Americans wager an estimated $7 billion a year on

the tournament. That is $1 billion more than the Super Bowl.

Also, consider the average ticket price at face value for the final four in

Indianapolis is about

$1,400 per person with fees up to $500.

Of course if

Kentucky

gets in, from the neighboring state, the scalped price may have no ceiling.

Finally, the economic impact of the NCAA tournament for host cities

generates millions and millions of dollars in local revenue not to mention the

Friday through Monday night schedule for the Final Four, meaning people will

spend four days to see two games.

Because of the complexity of the money trail, I am including an excellent

report done by Bloomberg Business on the business of money and the NCAA March

Madness. You would do well to review it

in detail.

March Madness Makers and

Takers

The way the NCAA

distributes the staggering revenue from the basketball tournament has created a

polarized system where some schools make money and others just take it.

By David Ingold and Adam

Pearce | March 18, 2015

Twenty five years ago, the NCAA

decided something had to be done about March Madness money. The year before,

CBS agreed to pay a record $1 billion to broadcast the 1991-1997 tournaments.

That was fine with the powerhouse basketball schools that routinely made it

into the postseason: Under the rules at the time, they divided most of the revenue

based on the number of games they won.

Conference officials feared that without a change, a handful of schools would

get rich while others got nothing, and the student athletes competing in the

tournament would face increasing financial pressure to win games.

Annual TV revenue from NCAA Division I men’s basketball

tournament $800 million CBS and Turner Broadcasting begin $10.8 billion ,

14-year deal Basketball Fund goes into effect after CBS nearly triples annual

revenue to $143 million ,TV rights switch to CBS from NBC Source: NCAA reports

Note: Chart shows the average annual rate over the course of a contract.

The Basketball Fund Is Born

So in 1990 the NCAA created the

“basketball fund,” a plan intended to more fairly divvy up tournament revenue

and parcel it out among the country’s Division I schools.

The new plan cut the amount of the payout that’s directly tied to teams’ wins

and losses. Most of the tournament’s TV revenue is now earmarked for things

like academic programs and financial assistance for student athletes. Even

schools that don’t play in the postseason get a cut.

The remaining amount makes up the basketball fund—and it’s no small pot. Last

year the fund totaled about 28 percent of the tournament’s TV revenue, or about

$194 million. These coveted dollars are won or lost on the basketball court,

and the battle among schools to claim them accounts for a lot of the Madness

each March.

The tournament TV contract brought in $700 million in 2014…

$498 million went to Division I schools… with $194 million given via the

basketball fund… $199 million this year … and that amount keeps growing.

How It Works

Teams earn a “unit” for every

tournament game they play up to the championship game. So a team that makes it

to the final four will earn five units. Each unit is worth a specific amount

each year. Instead of paying schools directly for the units they win, however,

the NCAA now gives the units to a team’s conference, and the conference is

responsible for distributing the money to its members. A conference can divide

up the money however it wants, but the NCAA suggests schools evenly split the

payout, and most conferences follow the recommendation.

The End of the $300,000 Free

Throw

One goal of the basketball fund

was to reduce the financial impact of individual wins and losses. Under the old

system in which schools were paid each year for their wins, a player who missed

a single game-winning free throw cost his team $300,000 or more. The fund

changed that by spreading out the tournament payments over six years; and since

that money is also split among the dozen or so teams in a conference, the

dollar value attached to any single game is diluted.

Every unit won in 2015 will be worth at least $1.6 million over six years. For

a strong team like Kentucky,

which might earn as many as five units if it makes it to the final four, that

once meant a massive payout at the end of the tournament. Under the basketball

fund, those units will be split with the other 13 schools in the Southeastern

Conference—dropping the per-school value of its units earned this year to about

$560,000 over the next six years.

Conferences Are Key

One big effect of the fund is

that it shifts the emphasis from winning teams to winning conferences. All 350

Division I teams will get a cut of this year’s $200 million basketball fund—but

strong conferences with many winning teams will rack up more units and take

home a much bigger share of the pile.

The nation’s top basketball programs have historically been in one of six major

conferences: the ACC, Big East, Big Ten, Pac-12, Big 12, and SEC. These

conferences only account for 20 percent of the teams in Division I, but they’ll

likely receive about 60 percent of the basketball fund payout this year.

The fund is supposed to be about rewarding performance, and it’s fitting that

the top programs will receive the largest cut of the money. But the strongest

conferences also include schools with weak basketball programs—and they get an

equal cut of the winnings even if they didn’t play a single game in the

tournament.

Basketball Fund earnings by conference, 1991 - 2015

A System of Makers and Takers

This focus on conferences instead

of teams has resulted in a system of makers and takers, where colleges in a

conference lean on a few key schools with powerful basketball teams to earn

money for everyone else.

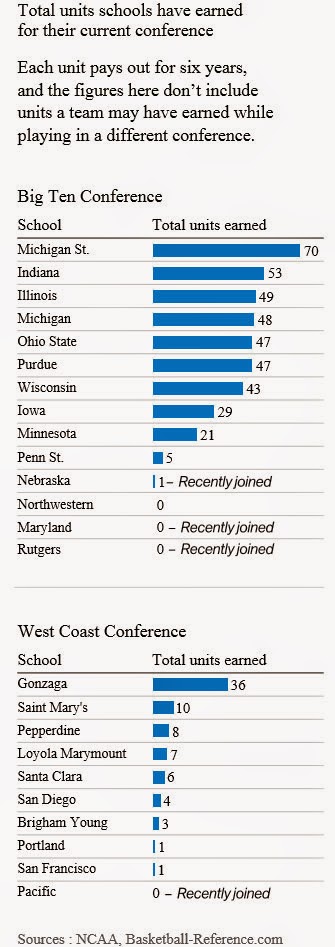

Take Michigan State,

a Big Ten school that’s earned 21 units during the current six-year payout

period. That translates to about $5.1 million for the Big Ten in 2015 alone.

After its earnings are lumped together with the rest of the conference and

equally doled out, MSU will get back one-third of the amount it’s put in. Other

top makers include Duke, Kansas, Kentucky, and North

Carolina.

This effect is magnified in smaller conferences, where a single team could be

responsible for the bulk of tournament appearances. Gonzaga University

plays in the West Coast conference and is responsible for half of its revenue.

It gets back an even smaller share, roughly 20 percent of what it contributes.

The inverse can be true for weak programs in strong conferences. An extreme

case would be Northwestern

University, which also

plays in the Big Ten. Unlike Michigan

State, Northwestern has

never made it to the NCAA tournament – not once since 1939.

Despite contributing zero units over the last 30 years, Northwestern has

received an estimated $24.5 million from the fund. This year, the school will

receive roughly $2.2 million, the same amount as Michigan State.

The chart below compares how much schools have earned for their conference and

how much they've gotten back. It assumes conferences equally split their

basketball fund revenue like the NCAA suggests. Looking at all the schools

together, it's clear that some are getting back a lot more than they put in.

Makers and takers by conference, 1991 - 2015

Movers and Shakers

Schools are continually changing

conferences, typically to improve their financial situation. Though

football-related money is the biggest motivator, all that jumping around also

has a big impact on the basketball fund, since schools rely heavily on one

another for units. Conferences with multiple earners can tough out the loss of

a powerful team. But the departure of a breadwinner can mean a huge financial

hit for weaker conferences.

Take the Horizon League, a mid-sized conference with schools from the Midwest that doesn’t have the depth of the ACC or Big

Ten. Twice the conference has lost its top earner to the Atlantic 10, a more

financially attractive conference. Xavier left in 1995, Butler in 2012. The last of the units Butler earned for the

Horizon League expire in 2016, and if another program doesn't step up, the

League’s revenue could drop to $1.6 million in 2017 from $5 million in 2011.

The West Coast conference now

faces a similar situation with Gonzaga

University. Located in Spokane, Washington,

Gonzaga earns more than half the conference’s units and is a #2 seed in the

tournament. A strong March Madness showing could increase its attractiveness to

more powerful conferences. The school is already rumored to be a contender to

join the new Big East. That leaves West Coast schools to cheer Gonzaga's

success, count the millions it brings them, and pray everything stays the same.

.